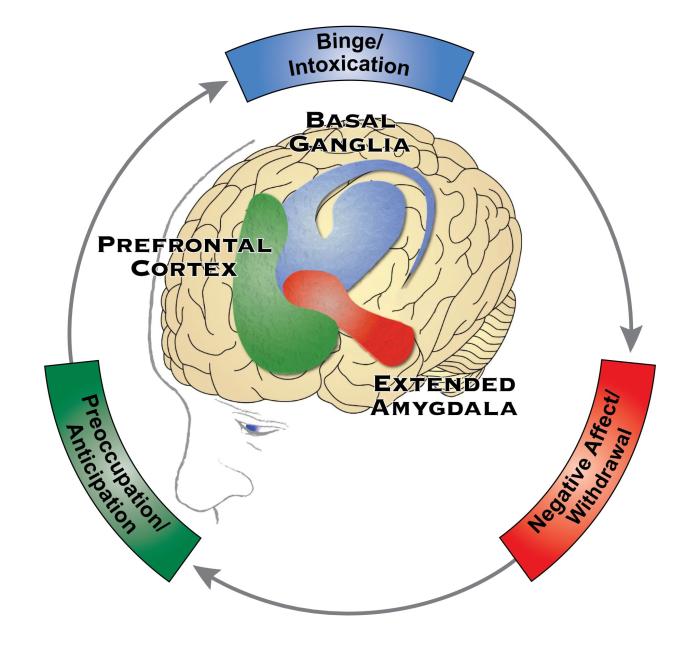

There are three major components to the pathophysiology of addiction

Neurobiological (ˌnu̇r-ō-ˌbī-ə-ˈlä-ji-kəl ). It’s a mouthful, but it is the most succinct and accurate way to describe the pathophysiology of addiction. In 2016, Dr. Nora Volkow (Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA]) and her team published a groundbreaking paper describing the disease model of addiction.1 This landmark article shifted the way many healthcare professionals think about and treat addiction. The pathophysiology of addiction includes three major components: binge / intoxication, negative affect / withdrawal, and preoccupation / anticipation.

Given that an estimated 40 million people (roughly the population of Florida and New York combined) 12 years old and older have a substance use disorder, all of us know and regularly interact with people who have an addiction to drugs or alcohol. Health professionals who do not understand the pathophysiology of addiction can (unintentionally but unfortunately) worsen the stigma and reduce the likelihood that people will achieve recovery.

First, let us lay a foundation with a few definitions:

Dependence is the state of being influenced or determined by another. In the case of substance use, the person would not feel normal without taking the substance.

Addiction is a chronic, relapsing brain disease that is characterized by compulsive behavior, such as seeking and using an addictive substance or engaging in a behavior, despite harmful consequences.

Substance use disorder (SUD) is the recurrent use of a substance that causes significant functional impairment, including negative health consequences and problems at home, work, or school.

I include these definitions to make sure we are all on the same page and using these terms in the right context. Dependence is an important one to point out because dependence alone does not mean a person has an addiction. For example, I have been drinking a cup of coffee in the morning for most of my adult life. If I do not drink my morning coffee, I will (more than likely) have a withdrawal headache. A withdrawal headache is uncomfortable but not serious. It indicates that I’m dependent on caffeine to feel “normal.”

The terms addiction and SUD are similar and overlapping concepts. Addiction refers to the cyclical, repetitive, and compulsive nature of the disease. Individuals can develop an addiction to many things. Gambling. Gaming. Dermatillomania (skin picking). Chewing ice! SUD is a specific type of addiction that causes impairment and dysfunction, and the person is unable to stop the substance use on their own.

Dopamine is a key player in the development of addiction. (See the article Motivated by Dopamine by Stuart T Haines). In short, the behavior or substance use releases dopamine in the brain. Dopamine plays a central role in our natural reward system, prompting us to seek food, water, shelter, and sex. It also prods us to nurture our young. Thus, dopamine is critical to our survival!

Addictive substances often mimic a natural neurotransmitter, stimulating an endogenous receptor in our brain, and potentiate dopamine release. Examples include opioids, cannabis, alcohol, and nicotine. Amphetamines and cocaine release abnormally large amounts of dopamine. This likely explains why stimulants are more addictive than other substances. Stimulants can cause as much as 100 times more dopamine release when compared to our natural reward system. Other substances range between 10 and 50 times more.

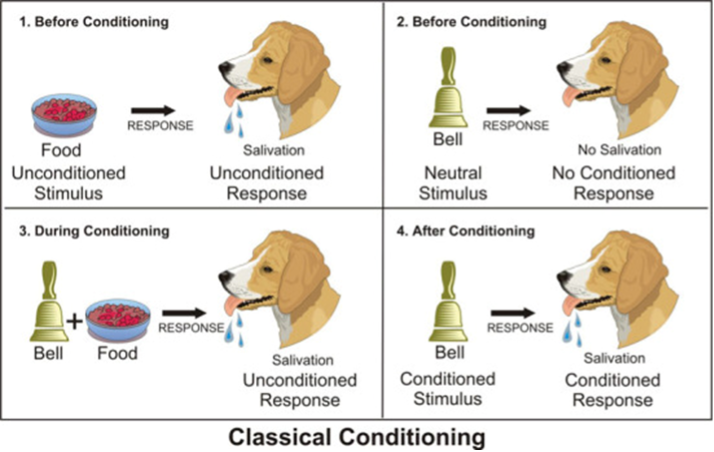

Another key element of addiction is conditioned response. You probably remember Pavlov’s dogs.

Dogs salivate when they see food. They anticipate eating the food, so their bodies are preparing for it. And they are motivated to consume it. This “unconditioned response” is created by the natural reward system. We are all motivated to eat in order to survive. In Pavlov’s experiment, he began announcing the arrival of food with a bell. At first, of course, the dogs didn’t know what the bell signaled – it was a neutral stimulus. But over time, by repeatedly ringing the bell as food was being served every day, the dogs learned that the sound of the bell was associated with food. Thus, the neural pathways in the dogs’ brains were being “conditioned” to respond to the bell in a way that was similar to food. Eventually, when the bell rang, the dogs’ mouths would salivate, even when food was NOT presented.

At this point, you might be saying, what’s your point? But when you see this picture, what is the first thing that comes to your mind?

It’s “just a sign”, right? But it is probably associated with all sorts of things in your brain. Perhaps a favorite menu item. A funny story. Or maybe thoughts about the obesity epidemic. Through repeated exposure to the sign, your brain has created neuronal tracks that stimulate certain thoughts. It might even trigger your natural reward system. Your brain is very good at noticing patterns and anticipating.

The brain is always looking for associations and patterns to release dopamine. A delicious piece of chocolate cake -> release dopamine; a funny TV show -> release dopamine; an enjoyable conversation/laugh with a friend -> release dopamine. The brain notices the association and subconsciously puts the circumstances of these events together. For example, the last time you and a friend had an enjoyable conversation, there was a song playing. The next time you hear the song, you might have a brief recollection of the event, you might smile to yourself, and you might be motivated to call your friend. The trigger (hearing the song) might induce a small release of dopamine, motivating you to initiate action toward recreating the previous experience. There is nothing wrong with calling your friend and maintaining a close relationship. In this case, the release of dopamine has resulted in a positive behavior that will improve your survival.

But this can work against you. When a person repeatedly uses a substance or engages in a behavior that releases a lot of dopamine, it can develop into a cycle that is exceedingly difficult to stop. The person begins seeking the substance far more than the natural rewards would ordinarily promote because the brain becomes accustomed to a larger and larger amount of dopamine. The brain adapts. Without these high levels of dopamine, the person doesn’t feel normal and has compulsive thoughts about the substance or behavior. Which brings us back to the addiction cycle.

Binge and intoxication

Dopamine production and release in the ventral striatum (limbic and nucleus accumbens)

Conditioned responses are formed and reinforced

Dopamine release becomes anticipatory through association with triggers and cues

Hedonic adaptation (substance is now needed in larger amounts in order to feel “normal”)

Withdrawal and Negative Affect

Diminished euphoria and then dysphoria

The amygdala is activated – this promotes a sensation of fear

Habenula is activated – triggers misery-fleeing2

Consumes substances or engages in behavior to avoid dysphoria

Preoccupation and Anticipation

The hippocampus (memory) and anterior cingulate (planning, organization) are activated

The orbitofrontal cortex (executive function) is impaired, diminishing the ability to resist cravings

Compulsive substance use occurs and perpetuates the cycle of addiction

There are some specific risk factors that have been identified in addiction research.3,4 Family history is a significant one. If a family member has a SUD or addiction, there is a much higher risk of developing one. Early exposure is another, particularly if the exposure occurs in adolescence when the person’s brain is still developing. Environmental stimuli can also increase the risk. For example, a person’s environment teaches them that using substances is acceptable or even encouraged when “having a bad day.” A mental health problem or trauma also increases the risk as some patients ‘self-medicate’ their depression or anxiety rather than developing more healthy ways of coping or receiving treatments that are unlikely to promote addiction. In people with impaired executive function, such as those with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), the risk of SUD and addiction is also higher.

The bottom line: addiction is a disease. Addiction is not a lifestyle choice; any more than cancer, diabetes, or osteoarthritis are choices. Behaviors contribute to all of these diseases, but no one chooses them. Similar to other diseases, addiction causes dysfunction and impairment. Like other chronic diseases, addiction has proven risk factors, genetic predispositions, and a pathophysiologic model (the addiction cycle). As the disease progresses, the symptoms become stronger and harder to treat. Thus, addiction becomes progressively worse as the neural pathways are recurrently reinforced. Patients who struggle with addiction experience cravings or triggers (thoughts of use) even when they are in recovery for many years. The associations in the brain persist. And like other chronic diseases, there are medications that help. Medications can lessen the impairments, reduce the cravings, and disrupt the addiction cycle.

When we understand that addiction is a disease, we are more likely to offer help, display compassion, and be a supportive advocate to those in need.

References

Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiological Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 363–371.

Batalla A, Homberg JR, Lipina TV, et al. The Role of the Habenula in the Transition from Reward to Misery in Substance Use and Mood Disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017; 80: 276–285. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.03.019.

Galanter M and Kleber HD. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment. American Psychiatric Publishing, 2015.

Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, and Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry, 11th edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2015.