Substance use disorder leads to a lot of physical and psychological suffering. And it’s a disease that is criminalized.

A lot of people are waking up to the fact that punishment doesn’t cure substance use disorder (SUD). And the threat of punishment doesn’t prevent addiction.

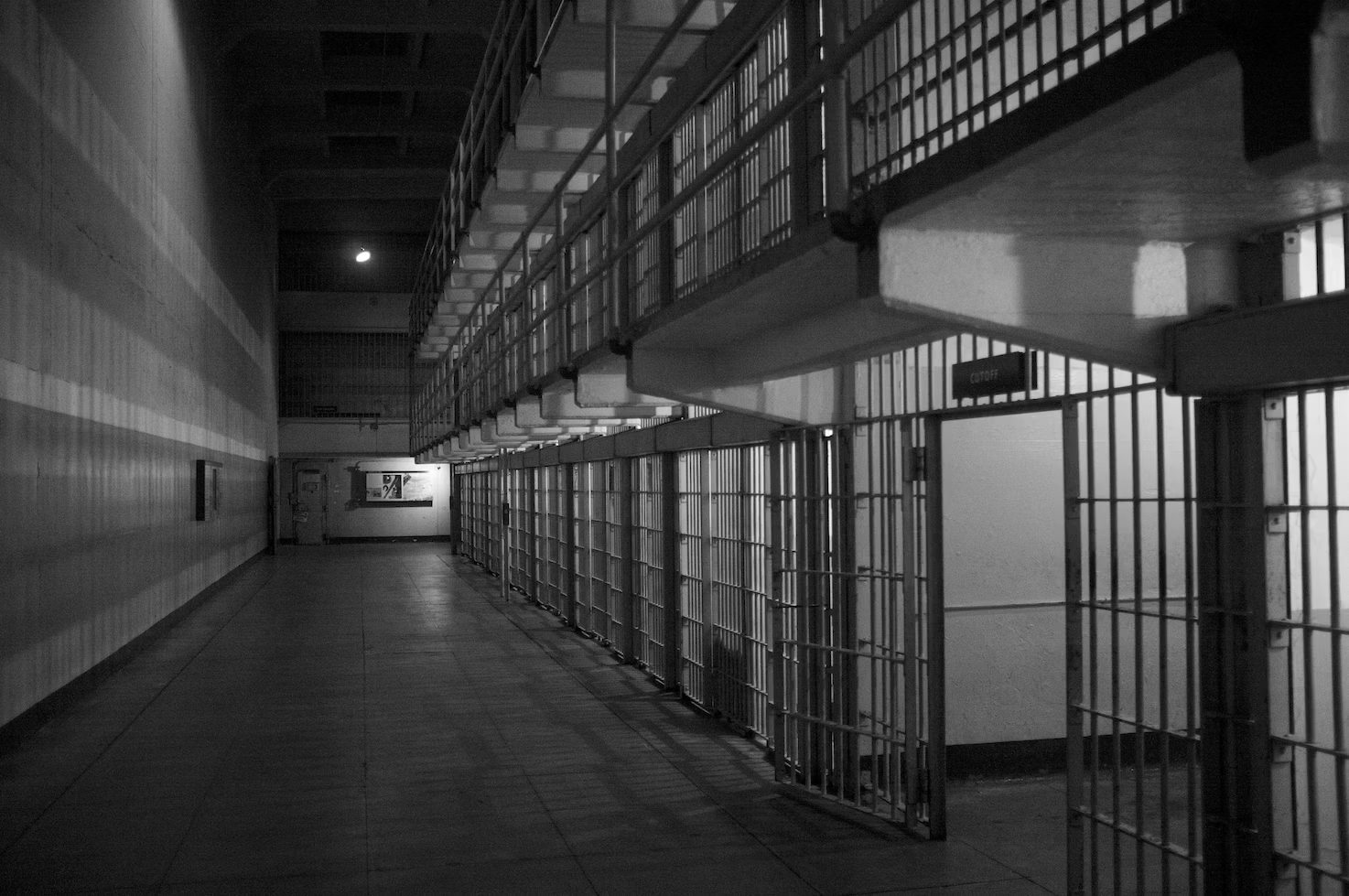

The United States has more people incarcerated than any other nation on earth. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, there were 2.3 million people in the United States in jail or prison in 2019.1 That translates into a rate of about 0.7% of the population, or 698 per 100,000 people. It might not sound like a lot, but it’s higher than any other country. Most European countries have rates of less than 100 per 100,000 people. The rate of incarceration in Finland and Sweden is just 57 per 100,000 people (that’s more than 10-fold lower than in the US). In the United Kingdom, it’s 77. And for our friends to the north, Canada, the rate is 114.

And rates of incarceration within the United States vary wildly. Mississippi, Louisiana, and Oklahoma have the highest rates of incarceration (all above 1000 per 100,000 people). While states like Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Minnesota have consistently had rates less than 400. Which is on par with South Africa, Brazil, and the Russian Federation. So, it’s not something to brag about.

Drug-related offenses and crimes fueled by drug and alcohol use are among the most common reasons people are incarcerated.2 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, police were making more than 1 million drug possession arrests each year. And drug-trafficking convictions are a defining feature of the Federal Prison system.3

Systemic racism also plays a critical role in criminalizing drug use and compounds the health inequities seen in our society.4 Suburban White people are often portrayed in the media as “victims” of the medical system that prescribed opioids or other addictive substances. Black and Hispanic patients, on the other hand, are often depicted in TV and movies as people engaged in illicit drug trade. Black and Hispanic people have less access to medical professionals willing to treat SUD or provide evidence-based treatments, like buprenorphine. Moreover, providers are more reluctant to prescribe medications to people from marginalized communities due to fears of diversion. Finally, people of color are more likely to be incarcerated for drug-related crimes, even in cases where similar criminal offenses have been committed.5

People trapped in our criminal justice system often have lots of unmet needs – social, psychological, and physical. Unfortunately, few local jails or state prisons have the resources or expertise to treat individuals with SUD. An estimated 50% of those in state prisons have a SUD before their arrest, but only a small fraction (10%) receive any kind of treatment, and a very small percentage receive medication-assisted treatment (MAT). The number of prisoners who died from acute intoxication or withdrawal while in jail increased by 400% between 2000 and 2018. Jails and prisons are just not well-equipped to address the underlying causes, and once released, most people convicted of a crime don’t receive SUD treatment. So, it’s little wonder that recidivism is high.

Now, this essay is not intended to be a political statement about whether we should or should not be “tough” on crime. Rather, my intention is to question our cultural beliefs about substance use and addiction. It’s widely considered a moral failing to use “drugs.” And we believe that those who use “drugs” should be punished. However, there is a bit of hypocrisy in that some substances are more socially acceptable than others. Like alcohol (ethanol), tobacco (nicotine), and coffee (caffeine). And, in recent years, cannabis (THC and CBD). So, what is considered acceptable and unacceptable is determined by social norms, not their potential to cause harm. Tobacco use was considered acceptable 40 years ago. Today, tobacco use is considered socially unacceptable, and its use is restricted to certain physical locations. But we haven’t made tobacco use a crime. We tried to criminalize alcohol use in the United States (18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution). But, by most accounts, that didn’t work out so well. While alcohol consumption was curtailed during Prohibition, injuries and deaths from criminal activities, as well as contaminated illicit sources of alcohol, soared.

So, criminalizing drug use has unintended societal consequences. But for the person who gets ensnared in the criminal justice system, it makes the vicious cycle of addiction so much worse. Not only does the SUD go unaddressed (in most cases), but once released, the “offender” is less likely to get a job (leading to poverty) and more likely to be ostracized from social circles that might have a positive influence on their lives. The stigma of addiction is compounded by the stigma of having a criminal record.

There are many enlightened police (individuals and departments), prosecutors, and judges who recognize that substance use is the root cause of so many crimes. For example, the Hinds County Circuit Drug Court in Jackson, Mississippi, provides an alternative to incarceration for substance-using offenders through judicially monitored treatment and intensive supervision.

As a society, we should not tolerate crime. And some substances are quite harmful, have significant addictive potential, and don’t have any well-established medical uses. So, I don’t think “legalizing” the sale and distribution of any and all substances is the way to go. That won’t solve the problem. But if we fail to address the root cause of these crimes, it comes at great cost to our society and the individuals who suffer from addiction.

Rather, I propose that we don’t put people with an SUD in double jeopardy. They need help. They need stability. They need structure. They need evidence-based treatment. They need to feel like they still belong in our society and that people are ready and willing to assist them. I believe health professionals have a special responsibility to model the way. However, research suggests that health professionals and those training to become health professionals share the same biases and beliefs that our society, at large, holds.6 Some introspection and working directly with people with SUD can change hearts and minds.

And that’s what this project is all about.

And that is how change happens.

One gesture.

One person.

One moment at a time.

-Libba Bray, American Author

References

Sawyer W and Wagner P. States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2018. Prison Policy Initiative. June 2018.

Sawyer W and Wagner P. Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2023. Prison Policy Initiative. March 21, 2023.

King R, Peterson B, Elderbroom B, and Taxy SA. How to reduce the federal prison population. Urban Institute. October 2015.

Jegede O, Bellamy C, Jordan A. Systemic racism as a determinant of health inequities for people with substance use disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2024. Published online January 17, 2024. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.4958

Sawyer W. Visualizing the racial disparities in mass incarceration. Prison Policy Initiative. July 2020.

Magnan E, Weyrich M, Miller M, et al. Stigma Against Patients With Substance Use Disorders Among Health Care Professionals and Trainees and Stigma-Reducing Interventions: A Systematic Review. Acad Med 2023. Published online Oct 6, 2023. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000005467